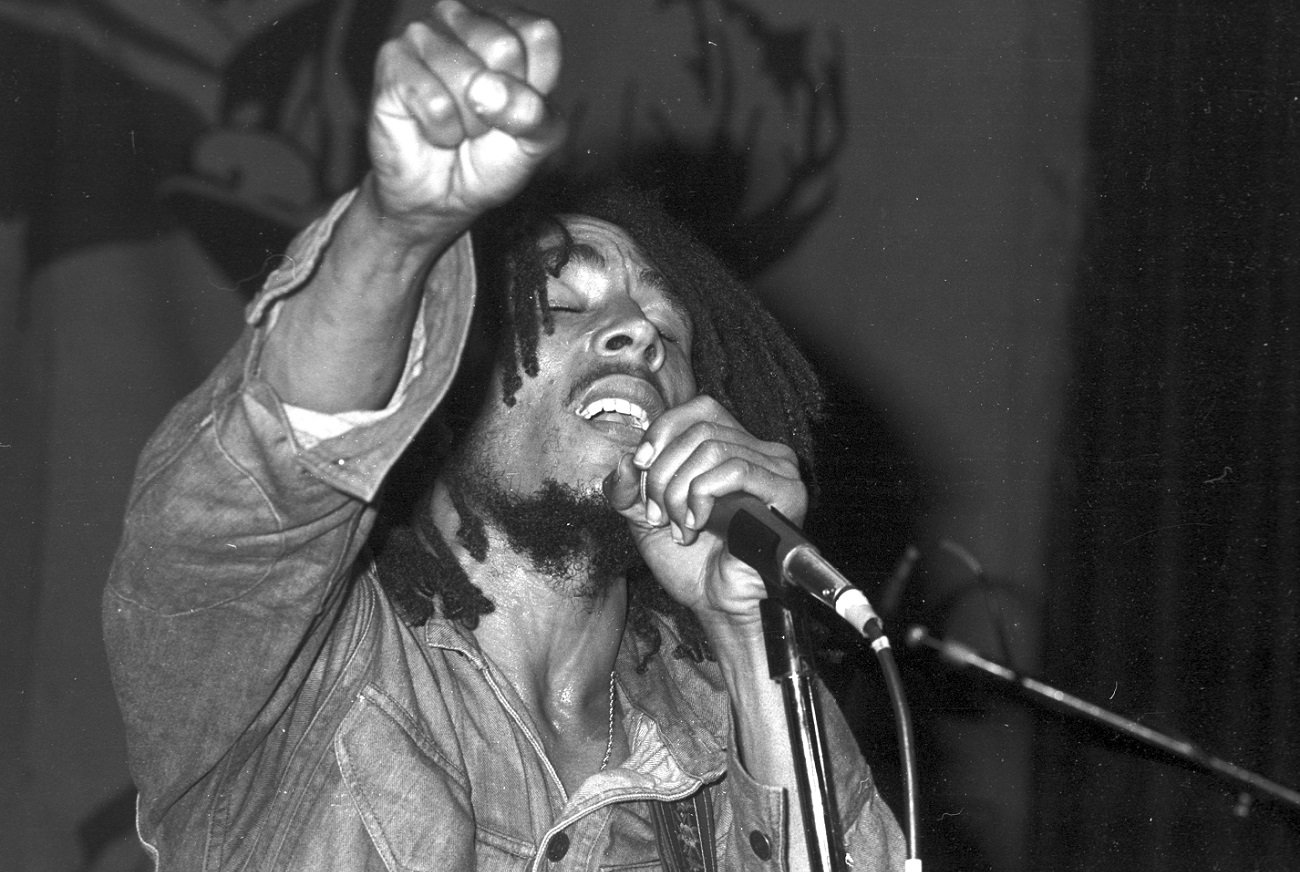

Classic Lines: Bob Marley ‘Feel[s] Like Bombing a Church’ on the ‘Natty Dread’ Album

Natty Dread (1974), the third album Bob Marley released on Island Records, stands out for a number of reasons. For starters, it was Marley’s first to feature him as the lead artist (i.e., rather than “The Wailers”). It was also the first LP Marley recorded without Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston. But nearly 50 years later, Natty Dread survives because of the power of Marley’s songwriting.

Along with “No Woman No Cry” and its feel-good bridge (“Everything’s gonna be all right”), Marley took his militant messaging to another level on the record. You certainly heard it on “Rebel Music (3 O’clock Roadblock)” and the stunning closer, “Revolution.” Meanwhile, Marley broke out one of his most memorable lines — that one about “bombing a church” — on “Talkin’ Blues.”

Bob Marley struck a nerve with his ‘bombing a church’ line from ‘Talkin’ Blues’

You can go by the airbrushed, Legend version of Marley or follow his evolution as a songwriter on the albums. If you choose the latter option, you’ll find Marley coming out strong with “Slave Driver” and “Concrete Jungle” on the Wailers’ first Island LP. And he kept writing revolutionary material (including “I Shot the Sheriff”) for Burnin’.

By Natty Dread, Marley was nearing his peak as a songwriter. On “Talkin’ Blues,” he takes on the character of a revolutionary, someone sleeping on the “cold ground” with “rock as my pillow.” In the second verse, Marley sings about being “down on the rock so long” he wears “a permanent screw” (i.e., frown).

But the narrator is defiant, he’s “gonna stare in the sun” and “let the rays shine” right in his eyes. It’s a religious image of sorts (seeing the light), but Marley’s narrator is seeing clearly in another way. “I feel like bombing a church,” he sings. “Now that I know that the preacher is lying.”

Marley didn’t expound upon that startling image in ‘Talkin’ Blues’

Marley’s “Talkin’ Blues” narrator hasn’t caught many breaks. He’s turned to the church for comfort and direction but found traditional religion sorely lacking. So there he is, pondering what it’d be like to destroy a house of worship run by a scoundrel.

“So, what then?” a listener would wonder. Marley more or less drops the thought in the song. “So who’s gonna stay and work,” he sings in the next (and last new) line. “While the freedom fighters are fighting.”

It’s another extraordinary image — the war is now raging, and somebody needs to tend the land at home — but that’s it as far as attacking any church goes. Marley lets his most provocative lyric hang in the air for the rest of the song.

‘Talkin’ Blues’ was credited to Leon Cogill and Carlton Barrett

The mysteries of Marley’s “Talkin’ Blues” don’t end with the lyrics. If you check the songwriting credits on Natty Dread, you don’t find Marley’s name on many songs. This track in particular is credited to Wailers drummer Carlton Barrett and Marley friend Leghorn Coghill.

Those credits perplexed even Marley’s bandmates, but there appears to be a simple, contract-related explanation. At the time, Marley hoped to avoid contractual obligations to manager Danny Sims by disguising his song copyrights.

So while Coghill and Barrett may have made contributions, Marley was clearly the primary songwriter and lyricist. Who else had the talent and guts to write that famous line in “Talkin’ Blues”?