Here’s What George Harrison Did to Make ‘Minority Music’ Heard

People like Ravi Shankar taught George Harrison many things. The legendary sitar player opened George’s eyes to a whole new world of music, and it fascinated him. After their first groundbreaking meeting, George made it his mission to support “minority music.” He used his influence over young people to spread the word about different kinds of music, and the world welcomed it with open arms.

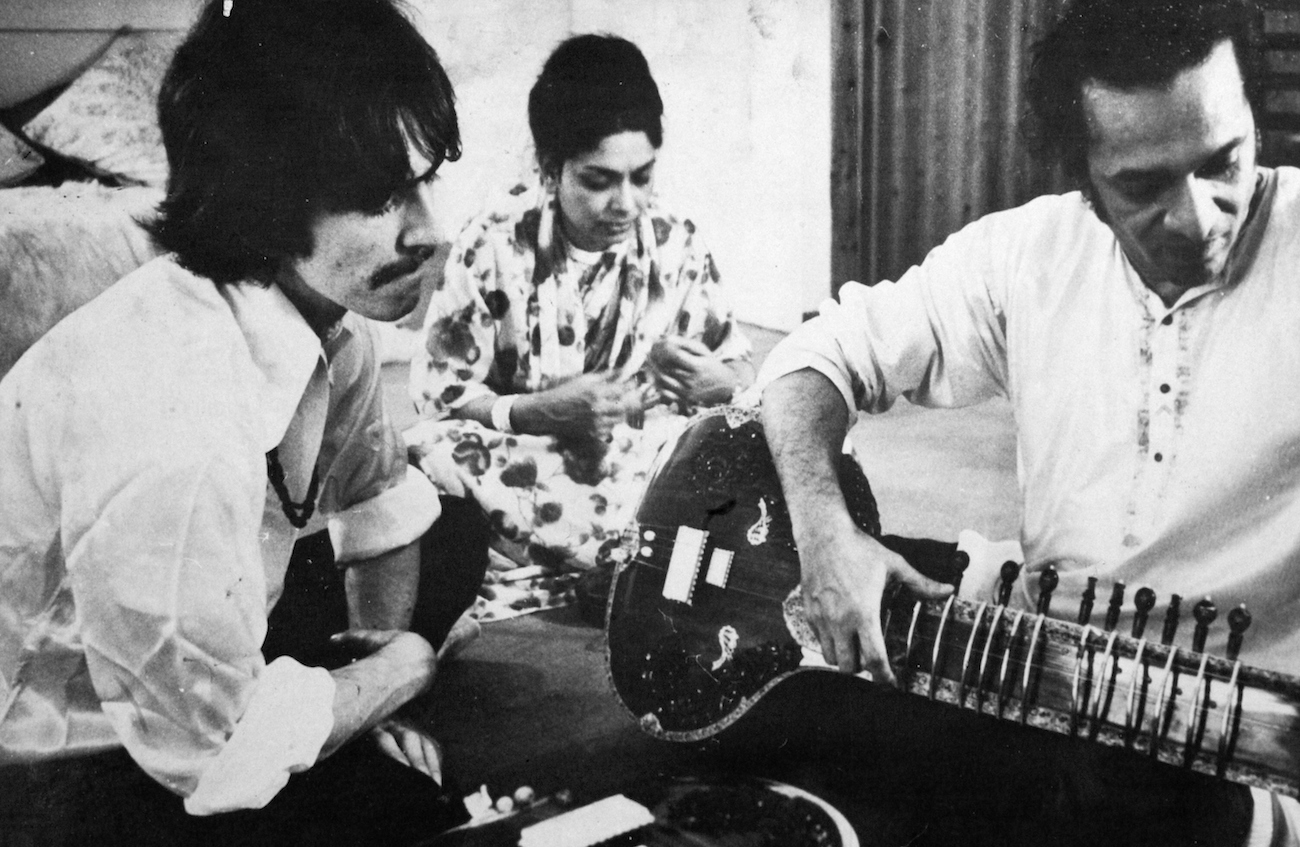

George Harrison met Ravi Shankar in 1966

In 1966, George met Shankar. At the time, he needed to regroup with his spirituality, as his fame was growing, so he traveled to India. At a friend’s house, George crossed paths with Shankar, almost like it was fate.

Speaking to Rolling Stone about his and George’s long-time friendship in 1997, Shankar said, “I had heard of the Beatles, but I didn’t know how popular they were. I met all four, but with George, I clicked immediately. He said he wanted to learn [sitar] properly. I said it’s not just learning chords, like the guitar. Sitar takes at least one year to [learn to] sit properly because the instrument is so difficult to hold. Then you cut your fingers to this extent [shows tips of two fingers – purple, with calluses]. He said he would try. He seemed so sweet and sincere that I believed it.”

George proved to Shankar that he wanted to learn. “[Harrison] gives me tremendous respect,” Shankar continued. “He’s very Indian that way. We are such good friends, and at the same time, he is like my son, so it’s a beautiful, mixed feeling.”

In Martin Scorsese’s Living in the Material World, George says Shankar taught him to find his roots. It was a great experience learning about Indian music, but Geoge knew he would never be as good a sitar player as Ravi.

George Harrison showed the world Indian music

George wasn’t going to be a sitar player, but he wanted to spread the word about it at least. As a “closet Krishna,” he wanted to make an album for the Radha Krishna temple.

On the back of the album, it said, “Your Transcendental Invitation: This album, with pictures and full text, produced by George Harrison, is a first recording of pure devotional songs in the ancient spiritual language SANSKRIT. Vibrations of these mantras reveal to the receptive hearer and chanter the realm of KRSNA consciousness, joyfully experienced as a peace of self and awareness of GOD or KRSNA. These eternal sounds of love release the hearer from all contemporary barriers of time and space.”

No one thought the album would be popular, but “Hare Krishna Mantra” made it on the radio stations in London and peaked at No. 12 on the U.K. charts in 1969. It was played at the Isle of Wight concert and during a football game in Manchester, England.

Beyond the successful mantra album, George worked with Shankar on many projects, including Chants of India. George also held one of the first and most popular celebrity benefit concerts, the Concert for Bangladesh, which was extremely popular. George and his friends played rock tunes while Shankar and other Indian musicians played their music. The live album won a Grammy.

George was one of the first Western artists to recognize the importance of world-music

In Living in the Material World, home video footage shows George asking house guests, “Why is minority music important? All the music that isn’t really sold in your local record store, in the top hundred. There is all this wonderful stuff.”

In the New York Times, Philip Glass wrote, “George was among the first Western musicians to recognize the importance of music traditions millenniums old, which themselves had roots in indigenous music, both popular and classical. Using his considerable influence and popularity, he was one of those few who pushed open the door that, until then, had separated the music of much of the world from the West.

“He played a major role in bringing several generations of young musicians out of the parched and dying desert of Eurocentric music into a new world. I have no doubt that this part of his legacy will be his most enduring. And not only that. He opened the doors to this new world of music with deep conviction, great energy and his own remarkable clarity and simplicity.”

His music and his skills in opening doors for world music do define George’s legacy. In return for many happy years of friendship, Shankar was there at George’s send-off when he died in 2001.