George Harrison on the Problem With Apple Records

George Harrison knew there was a problem with The Beatles‘ record label, Apple Records. Later, George was smart about artistic recruiting when he created his own record label, Dark Horse Records, and his film production company, HandMade Films.

George Harrison said The Beatles got control of themselves with Apple Records

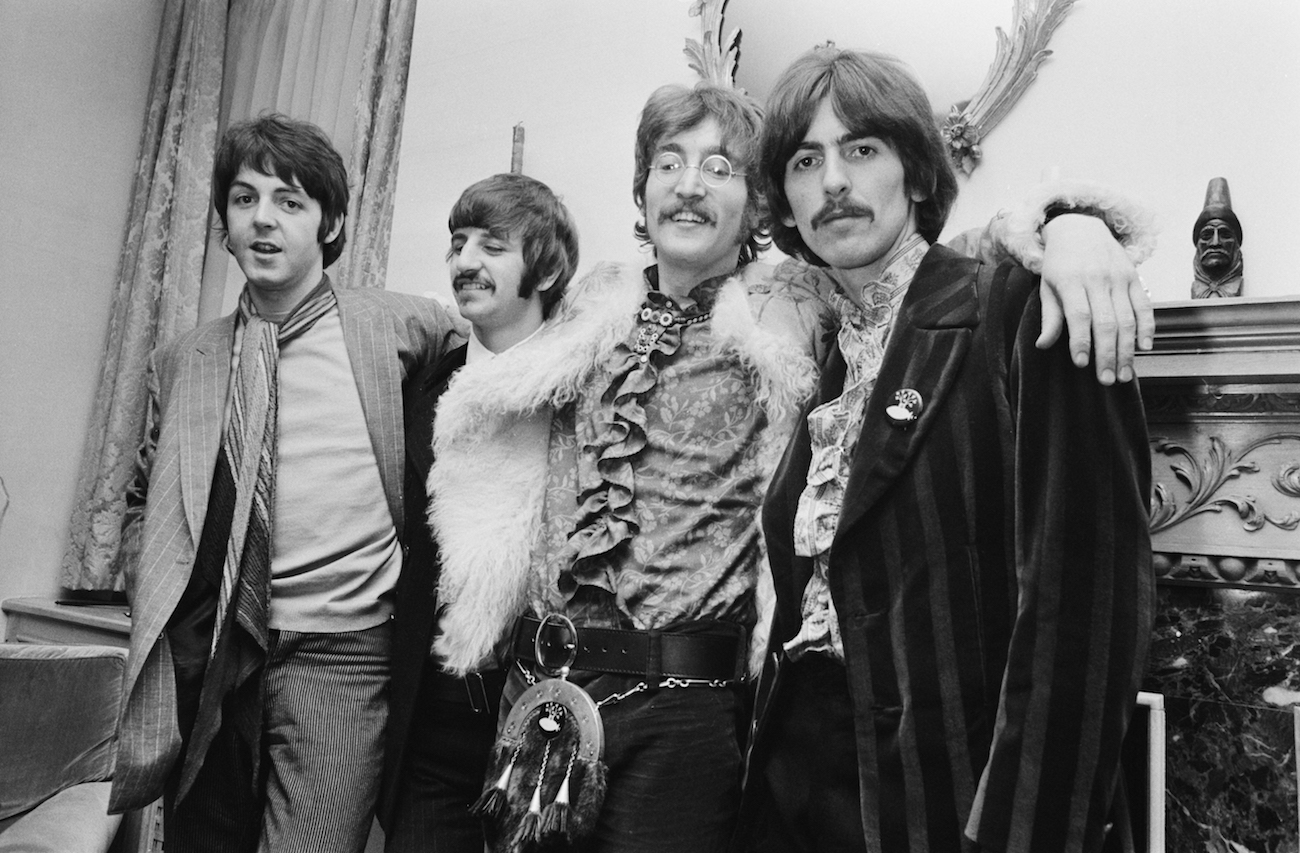

After their manager, Brian Epstein, died in 1967, The Beatles founded Apple Corps, an umbrella company for all their creative endeavors. Some sub-divisions included Apple Retail, Apple Publishing, and Apple Electronics.

When The Beatles returned from India in 1968, they founded Apple Records. They set out to be unlike any record company and wanted to give struggling artists a chance to create freely. According to George, The Beatles got control of themselves by creating Apple Records.

During a 1969 interview with CBC, George explained, “We found when our manager died, that we were involved with a hell of a lot of things that we didn’t particularly want to be involved in or that maybe we did want to be involved in but we didn’t want everybody else to be involved in.

“So really, Apple-all Apple was-it was Beatles limited, which we changed into Apple, and we tried to pull all our own affairs together into one company. We thought of the idea of being able to do records without having to go to somebody and say, ‘Please, can we do a record?’ which we still had to do even up to say two years ago.

“The whole sort of five years of our success was really trying to be ourselves and trying to get control of ourselves. Now, finally, we’ve got almost 100% control of ourselves, which again is a bit dodgy because then it’s the responsibility of whether we can be in control of ourselves.”

Apple Records liberated The Beatles. However, it also put them between a rock and a hard place too.

George, on the problem with Apple Records

In the early days of Apple Records, most of the label’s signees were acts that The Beatles personally discovered or supported. Sometimes, members of the Fab Four even wrote some signees’ songs. Some well-known signees included Mary Hopkin, James Taylor, Badfinger, and The Beatles’ friend, Billy Preston.

However, George recognized a problem with Apple Records. The record label’s business model was unrealistic. Apple Records couldn’t sign everyone who wanted to record music.

“But there was a mistake made when Paul and John announced from New York that what we want to do is help everybody-all those people have to go down on their knees to big businesses- we want to help them so that they don’t have to go down on their knees,” George explained.

“In actual fact, that was a mistake because, yes, we would like to do that, but the trouble is that to find people-really talented people-you have to go and find them. You come across them occasionally. The people who come and knock on your door from dawn until dusk begging for money and to get a break are usually the people who have no talent at all.

“So, we put ourselves-we snookered ourselves a little bit because we have all these people come in expecting us to just give them 50 thousand pounds, a hundred thousand pounds, to make a film or to do a record or do this or that but the thing is, we can do that, but only in moderation because if we don’t watch it or we’d run out of money, then we wouldn’t be able to help anybody.”

The Beatles had an innovative idea to give good music that hadn’t been given an opportunity to be heard. However, in terms of its financial standing, it wasn’t realistic.

George allegedly rejected Crosby, Stills & Nash for Apple Records

After inviting everyone with a song (or not) to Apple Records, The Beatles had to turn many people down. However, they turned down one act they shouldn’t have. According to David Crosby, George rejected Crosby, Stills & Nash for Apple Records.

Crosby tweeted, “Did not record for them…live audition…sang the whole first record in London to George and Peter Asher …Apple passed on a number one record there …..ahh well …everybody makes mistakes ….Bet they regretted it later.”

A fan replied, “Wow… I can’t imagine someone hearing ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes‘ at a live audition and deciding to pass.” Crosby responded that the trio was surprised too.

Graham Nash also told the story to the Guardian. “We had an apartment on Moscow Road in London, we were rehearsing the first record [Crosby, Stills & Nash, 1969], and we had our s***

down,” he said. “To hear ‘Suite: Judy Blue Eyes’ in our living room was pretty f***ing impressive. And they turned us down. So did Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel.”

In 1970, after The Beatles’ split, Apple Records fell to the control of Allen Klein, who dropped much of the label’s roster. So, no one was getting signed.

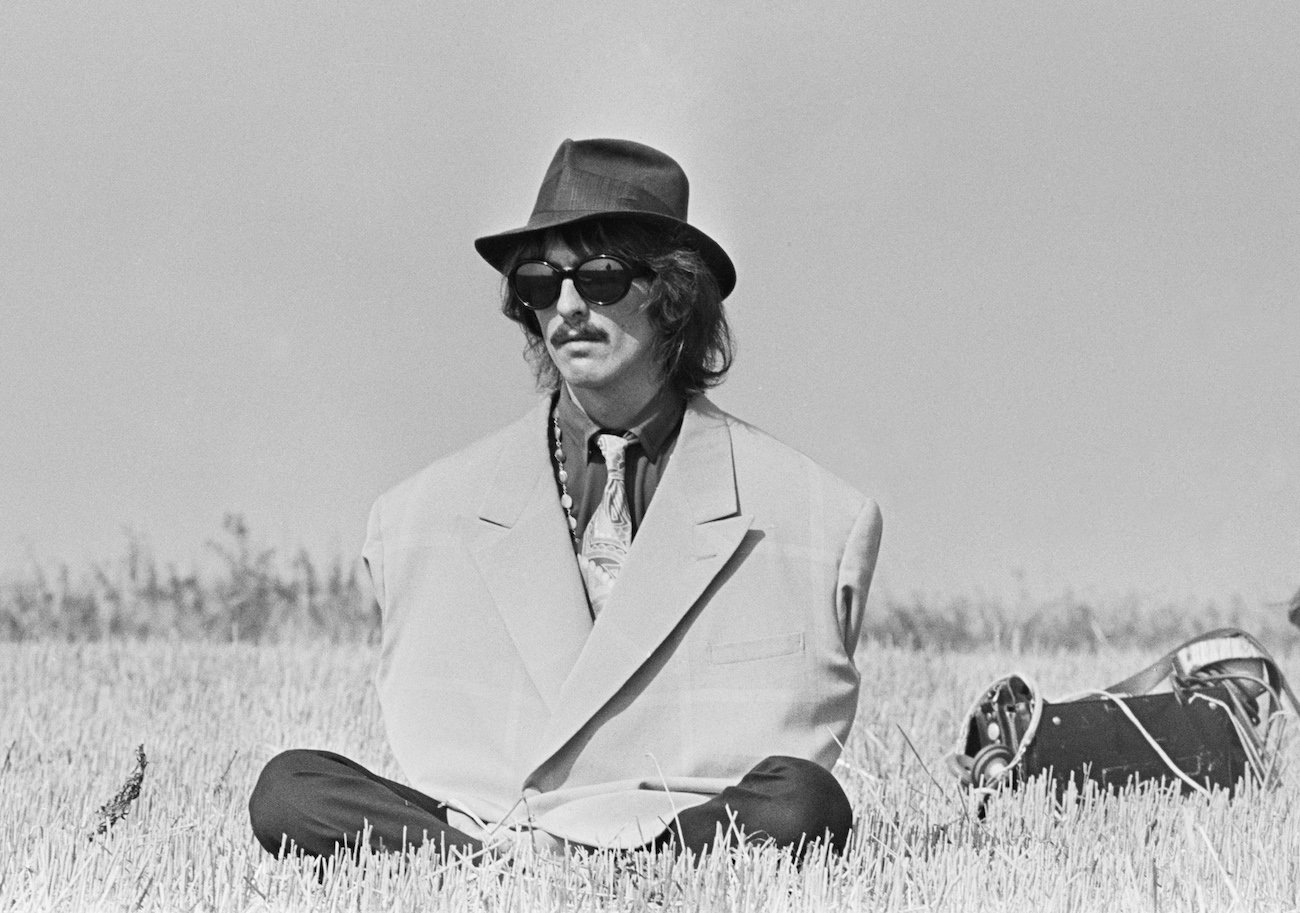

George later ran into a similar problem with accepting creative people

Later on, when George started his record label Dark Horse Records, and his production company, HandMade Films, he ran into a similar problem that Apple Records faced. He had to control the number of signees. With HandMade Films, there were so many scripts coming in, but they couldn’t make them all into films either.

He told Film Comment, “There are so many scripts coming in now. And, personally, I hate reading them. But a guy on staff named Ray Cooper serves as my ears. He’s also a musician, a percussion-and-drums player for Elton John, and I know I can rely on his being sensitive to the artistic side of things. There’s always a conflict between the ‘business,’ what people see as the brutal business aspect, and the ‘artistic’ side.

“Since I’ve been an “artist”—make sure you put that in inverted commas—and have Ray there all the time, it eases the problem a bit. If a couple of people on the staff all happen to like the same screenplay, then copies go out and everybody reads them and decides whether we’ll do it or not.

“I suppose Denis and I have the final say, but it’s rather a committee system. It takes a number of people to like a script before the red light turns to amber.”

So, George had a sensible plan to limit the number of scripts coming in. If Apple Records did that, maybe it’d still be a great record label.