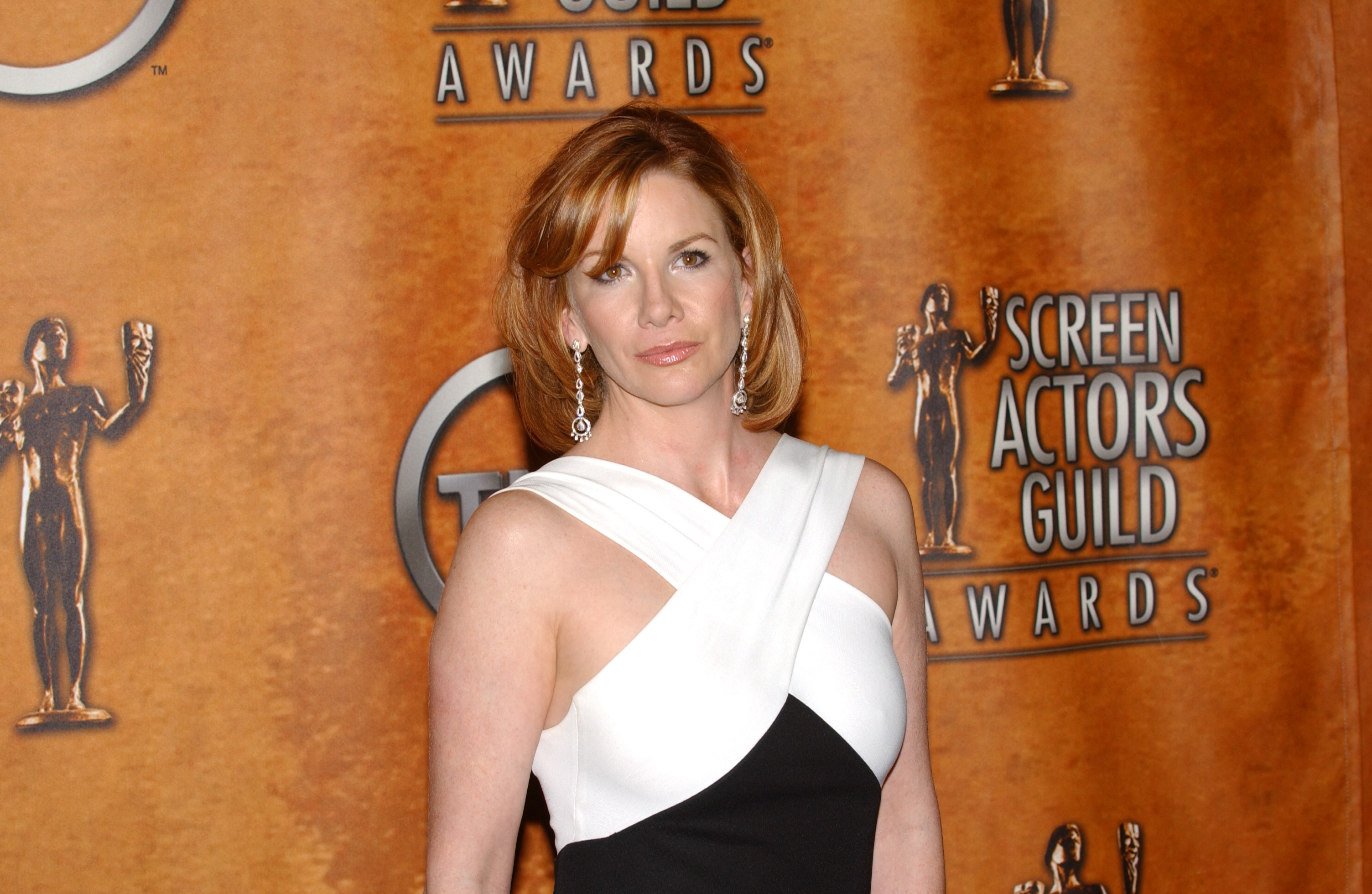

Inside Melissa Gilbert’s Brutal 3-Year Lawsuit Against Her 1st Husband and the National Enquirer

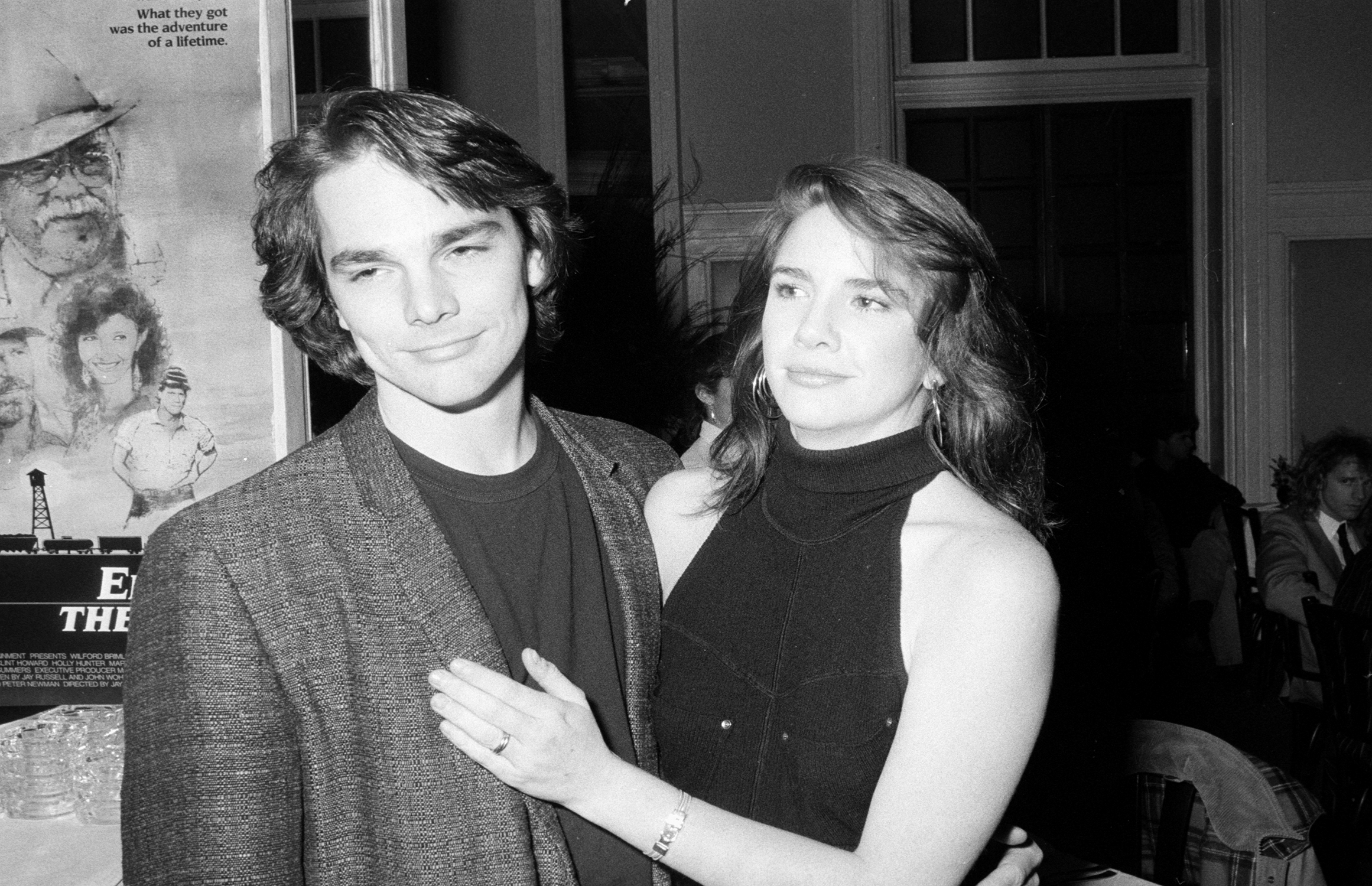

Melissa Gilbert has been in the public eye since she was 9 years old and became the star of Little House on the Prairie. She’s no stranger to appearing in tabloids. Through the years, she let the inaccurate stories go. They didn’t really hurt anyone but her so she let them slide. Then, in 1995, a story ran in the National Enquirer that quoted Gilbert’s first husband, Bo Brinkman, calling the Laura Ingalls actor a “deadbeat mother” to their son. He made claims that Gilbert says were simply untrue. So she sued the tabloid, as well as her ex-husband, and things got ugly. This is Gilbert’s perspective on the lawsuit.

The story in the National Enquirer

Not too long after Gilbert learned she was pregnant with her second child (though her first with her second husband, Bruce Boxleitner), she received a call from her publicist warning her that there was going to be a “scathingly bad cover story in the National Enquirer.”

“The tabloid quoted Bo as saying I was a ‘deadbeat mother,'” she wrote in her 2009 memoir, Prairie Tale. “They claimed Dakota [her son] ran up to strange women on the street and asked them to be his mommy. They said Bo had had to get up at night to feed him when he was an infant. It also said I refused to take care of him when he had the chicken pox, and I forced him to watch reruns of Little House.”

Gilbert had been in the headlines of tabloids many times before — “the tabloids had called me manipulative, accused me of having people fired on Little House, followed Rob and me like vultures, and paired me up with people I never dated” — but this time was different.

“It planted a seed,” she wrote. “For instance, Bruce’s relatives in the Midwest didn’t know this was untrue, and they received calls from people delicately inferring that maybe Bruce shouldn’t be having a child with me.”

Melissa Gilbert decided to sue the National Enquirer and her first husband, Bo Brinkman

Gilbert decided she wasn’t going to let this story go.

“I hired powerhouse attorney Larry Stein and sued the National Enquirer and Bo for defamation, invasion of privacy, and infliction of emotional distress,” she wrote.

Gilbert called the lawyers on the tabloid and her ex-husband’s side “cold, crude, and unflinchingly callous.”

“At one hearing in early September, I was plainly sick and uncomfortable,” she wrote. “I asked my attorney if we could postpone the session for another day. After he made the request, the attorneys for the National Enquirer and Bo conferred with each other, and then the Enquirer’s attorney said, ‘We’ll move forward. We have no sympathy for Ms. Gilbert.'”

Gilbert thought: “Okay, you motherf*ckers, game on.”

“I was already committed to seeking justice, but at that point I vowed to see the suit through and win, come hell, high water, or severe nausea,” she wrote.

Things continued to get uglier and uglier.

“Unlike me, the tabloid had limitless resources and money,” wrote Gilbert. “It was a mess, and it filled my otherwise perfect life with an unhealthy dose of daily stress. The stuff they threw at me was brutal. But I soldiered on, knowing I was in the right.”

Melissa Gilbert took Bo Brinkman out of the equation and reached a deal with the National Enquirer

When Christmas came around, Gilbert asked her son, Dakota (whom she shared with Brinkman), what he wanted for the holiday. He said he wanted his parents to get along. So Gilbert dropped the suit against her ex. But she continued to fight the National Enquirer.

“The suit would drag on for nearly another two years until finally we had to end it,” she wrote. “The cost was staggering, in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and by then all I wanted to find out was why—why they would print a story they knew was blatantly untrue and obviously damaging to my life and career, and my children’s lives.”

[During the course of the lawsuit, Gilbert gave birth prematurely to her second child. She blamed the stress of the legal situation.]

Gilbert’s attorney arranged a meeting between her and the National Enquirer’s editor in chief, Steve Coz. They met in Clearwater, Florida and spoke about the story and lawsuit. They agreed to not discuss the contents of their meeting, but Gilbert says she learned the decision to print the story was not a personal attack against her but, rather, a business decision. Though she did not get the justice she initially set out to pursue, both parties reached a deal and dropped the lawsuit.