‘When the Levee Breaks’: How Jimmy Page Recorded John Bonham’s Epic Drum Part

What else can you say about the John Bonham drumbeat on “When the Levee Breaks”? Maybe you think it’s the ultimate example of power and restraint; maybe you marvel at how it fueled a classic Beastie Boys rap 15 years later; and maybe you think it began the greatest closing statement on any album in rock history.

You’d be right on all three counts, of course. But all that has been said in one form or another about the classic Led Zeppelin track from the band’s fourth (technically untitled) album. And everyone who’s heard it can relate to these reactions.

But the making of “When the Levee Breaks” is almost the equal of the track’s impact in the annals of Zep lore. And it begins with the work of Jimmy Page, who doesn’t always get the credit other producers (e.g., “fifth Beatle” George Martin) did for recording the entire Led Zeppelin oeuvre.

When approaching “Levee” for the Led Zeppelin IV sessions, Page fell back on his battle-tested philosophy that “distance equals depth” while working far away from the studio settings other bands swore by.

Led Zeppelin recorded ‘IV’ in a converted poorhouse called Headley Grange

Before getting into the recording of “When the Levee Breaks,” you have to get a feel for the setting. For their previous album (Led Zeppelin III), the band had decamped to a former Headley (Hampshire, England) poorhouse from the 1790s that was converted to a residence in the late 1800s.

Known as Headley Grange, the band lived, worked, and recorded III in the immense building using a mobile recording studio parked outside. And after doing some work on Led Zeppelin IV in London, Page and the group went back to Headley Grange.

That’s where tracks like “Black Dog” and “Four Sticks” came together. But deep into their work on the album, a delivery arrived containing a second drum kit for Bonham. Instead of halting their current session, they told the delivery crew to leave it in Headley Grange’s huge hallway.

After a while, Bonham went out to test the kit. And Page heard a sound unlike anything he’d heard on record. “The sound was huge because the [hall] was so cavernous,” he told Brad Tolinski in Light and Shade. “So we said, ‘We’re not going to take the drums out of here!'”

John Bonham played to mics hanging from the 2nd floor

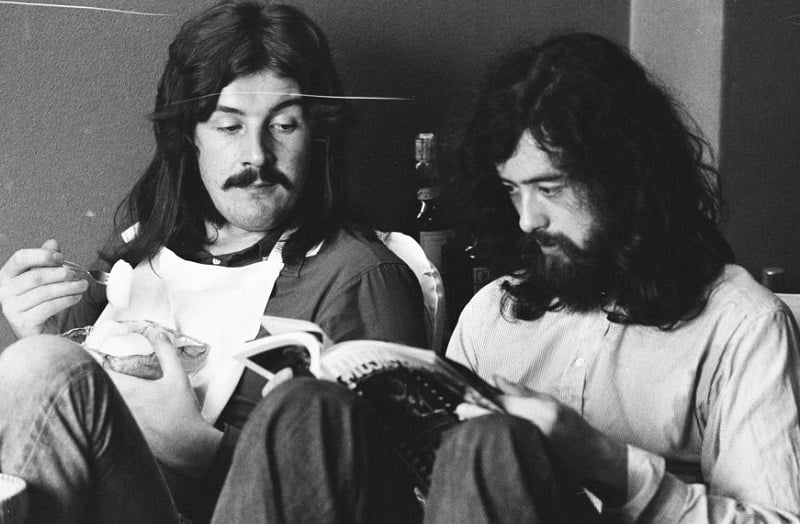

So with his powerhouse drummer pounding out the beat to “When the Levee Breaks” in a vast hallway of a country estate, Page had to figure out how to get the sound on tape. By then, he had Andy Johns (brother of Glyn, who’d done the debut Zep album) engineering.

According to Andy Johns (via Led Zeppelin: All the Songs), the sound resulted from experiments he made with Bonham one night when the band wrapped up an evening’s session. But either way, Johns hung microphones from the second floor of Headley Grange. Page said Johns made some modifications to the sound and they never had to mic the kick-drum.

This move continued Page’s philosophy of ambient miking for the drums. (Rather than putting microphones right on the instruments, he’d allow the sound to travel to another mic.) “Nobody was doing that,” he told Tolinski, before explaining his belief that drums “had to breathe.”

But recording the backing track was only part of the magic of “Levee,” which Page said he wanted “to make into a trance.” That required a special mixing technique — one which Glyn Johns heard and declared would never work on record.

After Page and Andy Johns had applied the phasing, panning, and a few other tricks at the end of “Levee,”, they played it for Glyn Johns. “You’ll never be able to cut it,” Page recalled Johns telling him (from a ’93 Guitar World interview). “Wrong again, Glyn,” Page declared with satisfaction.

Also see: When The Who’s John Entwistle Reportedly Came Up With the Name Led Zeppelin