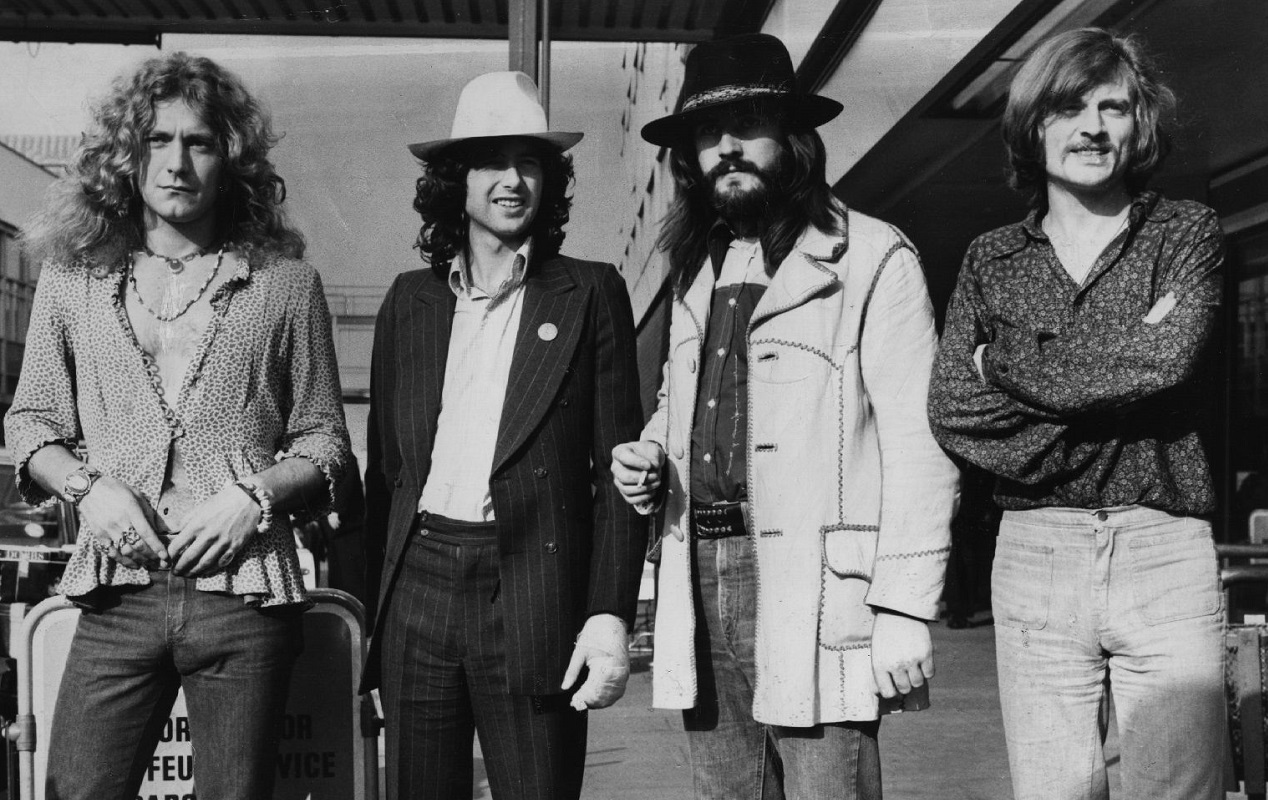

Why Led Zeppelin Didn’t Need a Chorus on Some of the Band’s Greatest Songs

Led Zeppelin didn’t always shy away from pop hooks and big choruses. You hear both on “Good Times Bad Times,” the band’s debut U.S. single and opening track to Led Zeppelin (1969). In the beginning, prominent choruses were part of the plan.

But as the band came into their own as songwriters, that changed. On Led Zeppelin IV, the only track with a big chorus was “Rock and Roll.” As for “Black Dog” and “Stairway to Heaven,” you found riffs and instrumental breaks where the choruses would normally go.

On Houses of the Holy (1973), listeners got more of that approach from Jimmy Page and his bandmates. “The Song Remains the Song” (the opener) began as an instrumental and didn’t stray far from its origins. On Physical Graffiti (1975), the stirring “Ten Years Gone” also started without lyrics.

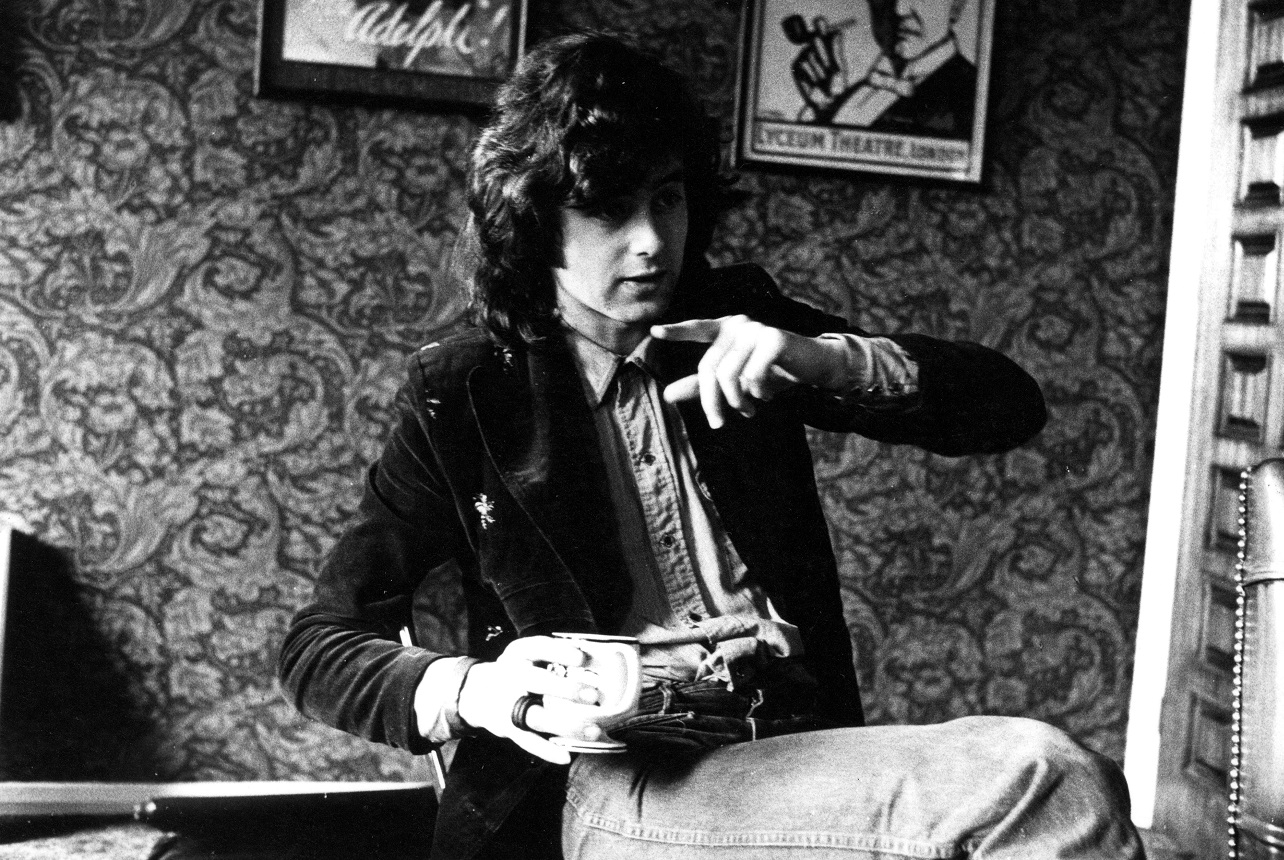

That was definitely part of Led Zeppelin’s master plan. Page, the primary songwriter in the band, didn’t write lyrics and wanted the entirety of the music to stick with listeners at the end of each track.

Jimmy Page said Led Zeppelin didn’t want to ‘retreat to the security’ of big choruses on every track

After the demise of Led Zeppelin, Page toured with Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, and others for the ARMS Charity Concerts. And at those shows he played an instrumental version of “Stairway to Heaven.” The lack of vocals didn’t blunt the song’s impact for audiences.

“Stairway,” of course, works in movements. At the spot where the chorus might come in the original, Plant sings “Ooh, it make me wonder.” Then those sections alternate and build until the furious finale. “Kashmir,” the band’s Physical Graffiti masterpiece, also charts its own direction.

In Brad Tolinski’s Light and Shade: Conversations with Jimmy Page, the Zep mastermind explained the band’s approach on these definitive tracks. “We wanted every part of the song to be important and have movement,” Page said.

“There was no need to retreat to the security of having a big chorus in every song. If you emphasize one part of the song, it trivializes the rest of the music.” For a master riff-writer like Page, there was more than one way to hook an audience.

Page believed a powerful riff could replace a chorus

Page took up the subject of choruses in a section of Light and Shade that featured a conversation between him and Jack White. After Page explained the Zep philosophy, White spoke of how something the riff of “The Wanton Song” could replace the chorus. Page agreed.

“A riff can take on the aspect of a chorus in a listener’s psyche,” Page replied. “When that happens, the whole song becomes one big chorus.” Anyone who’s gotten hooked by “Whole Lotta Love” or “Kasmir” will struggle to deny that.

Page saw the Zeppelin approach connected to the music of other places and historical eras. “The idea of a hypnotic riff as the prime mover of a piece of music has been around a long time,” he said. “Whether you’re talking about the Delta blues or music from Middle Eastern and African cultures.”